Usually, if I write about art (architecture, sculpture, painting), it is about modern art. Medieval churches and Renaissance castles, impressive as they are, are for me less interesting to write about.

I am making an exception for mills. Fueled by the interest of Australian family and American friends, I find the technology and function of mills as fascinating as the design of modern architecture.

Since the Middle Ages, the low countries have fought against the water and Dutch windmills played a major role in this.

Table of Contents

Lots of mills

When I was younger, I didn’t understand the fascination of foreigners for the Dutch mills. What was so special about them? They were everywhere and after all, there are mills in other countries as well.

However, mills are very special because they transfer wind into useful energy. As such this is not a big deal. Over 6.000 years ago, the Egyptians used sails to catch the winds that propelled their ships.

It would be no surprise if these ship-sails inspired mills. In the earliest windmills, all sails were connected to one and the same vertical stake.

This changed with the use of cogwheels. These wheels transferred the rotation of a horizontal axle to a vertical axle. The horizontal axle was connected to the sails of the windmills which we experience as characteristic and are used to produce what we now call ‘green energy’.

References to this type of windmill can be found in early medieval charters. For example, in July 1220, the nineteen-year-old Dutch count of Holland, Willem I, gave his twenty-nine-year-old wife, Maria of Brabant, the mills of Zierikzee.

Dutch mills are classified in several ways

Mills can be defined by:

- The energy source – water, wind, fuel, human muscles, animal force;

- Their function – sawing, grinding, creating polders;

- The construction method – standerdmolen, paltrokmolen, stellingmolen, wipmolen, bovenkruier, etc. (sorry, I couldn’t find a correct translation, so I kept the Dutch terminology).

A polder mill is also called a watermill, but there is a difference between a watermill that’s powered by water and a windmill that transfers water from one place to the other.

Another way of sorting is by product (corn, oil, paper, etc.) and there are even names for the different animals that were used, like a “rosmolen”. Ros is an old-fashioned Dutch word for horse. Enough to choose from!

Catching the wind

Some mills are built directly on the ground, others are on an artificial hill, or on top of a building.

The shape also differs, varying from stocky to high, with or without a wooden scaffolding. The latter is necessary for a high mill to allow the miller to reach the sails.

In addition to tradition, the environment and the usual wind direction largely determine the chosen shape. An artificial hill ensures that the mill can better capture the available wind.

Mills in art and literature

The 17th century was the Netherlands’s Golden Age, partly due to sources of energy that were readily available: wind and water. Jacob van Ruysdael was a refined Baroque landscape painter, who painted a lot of mills. The same impressive clouds he painted are in some of my pictures, although a painter can emphasize the drama even more.

Most people are familiar with the story of Don Quichote, fighting the windmills of La Mancha. Mills that can be admired to this day in the city of Consuegra in Spain.

My favourite part of the mills is the sign language

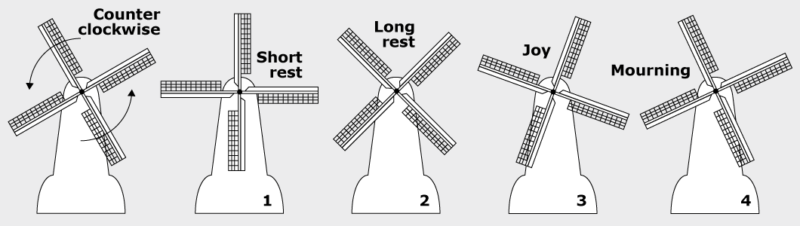

With the wicks, the miller could talk to the neighbourhood. It goes much further than the examples I give here, but since there are even dialects in mill-talk I’ll just mention the main signs: Keep in mind that the turning of the wicks is counterclockwise. That makes it easier to understand what’s meant by going up and going downwards.

- The wicks are placed as a cross – this means the miller is having a lunch break or is doing a chore somewhere;

- At an angle of 45 degrees – a long rest. In this position, the rain was the least likely to cause damage;

- Halting the wicks just before they would pass the highest point (going up) – joy and celebration. Sometimes emphasised by flags, garlands or coloured ribbons;

- Stopping the wicks just after the highest point (going down) – mourning and grief. If somebody had died they even turned the head of the mill in the direction of the house of the deceased person.

Adding the sails gave even more meaning to the signs. When for instance the miller didn’t have enough work, a certain way of folding the sails indicated people could bring their grain. The sails are adjusted depending on the wind.

Hotspots in the Netherlands

Mills are a national pride for many Dutch people and lots of groups of volunteers maintain a local mill with huge love and attention.

Some mills are still in use. The corn mill De Korenbloem in the village where I lived sold delicious whole wheat flour milled the traditional way.

The volunteers are often so enthusiastic that you only have to ask them one question to receive an hour of explanation. They know the terminology of even the smallest part. I always love it when people are so passionate.

You might be lucky and see a mill at work in a village so you can check it out. To be sure, however, it’s better to visit Kinderdijk and De Zaanse Schans.

Kinderdijk

The windmills of Kinderdijk are on the UNESCO World Heritage List. They are almost all identical and were built to pump out the water from the low-lying polder.

Mills have existed here since the 15th century, but they have been rebuilt over time due to fire or decay. The current mills are almost all from the 18th century.

The area is accessible 24/7 free of charge, but only on foot or by bicycle.

If you want to view the inside of a mill, there are of course entrance fees. Check the opening hours in advance and order your ticket online if necessary, because it can be quite busy.

As you can see in my pictures, I was here off-season. It was quiet then!

De Zaanse Schans

Unlike the windmills of Kinderdijk, those of De Zaanse Schans are not located in their historic location. They have been moved from the region into an open-air museum and placed together.

As a result, there is more variation in the Zaanse mills than in the Kinderdijk mills.

Some houses have also been moved and together the mills and houses now form a protected villagescape.

Typical for the region is the wooden construction and a certain colour of green that you mainly see on the facades of the houses.

In the article Postmodern Architecture and my 3 Favourite Heroes, you can see an example of a modern hotel, inspired by this tradition.

This area is also accessible for free 24/7. And like in Kinderdijk there are museums in the mills and houses.

Do you like Dutch mills? Tell me in the comment box below.

OMG. Nostalgia. These Dutch mills are so beautiful. And so well preserved throughout the country. I know of no other country where this is the case.

Not counting the numerous huge windmills that are trying to control the climate crisis! Although I guess these modern windmills owe a lot to the old ones.

Do people still live in them?

Yes, Christine, I agree they are beautiful. I don’t know of any inhabited mills personally, yet, there are about 150 mills in the Netherlands where people live in.

Most of them are so called poldermills that take care of the water management of the polder. There is a practical reason for inhabiting those mills, because water does not adhere to office hours and there can also be high water at night. 🙂

The other mills were more industrial, like small factories. The complete mill was dedicated to the process of, for example, grinding corn.

Thanks for your interesting question. I had never thought about it before!